My 1976 Guild F-212 XL is in need of a neck reset. The guitar is not damaged in any way. The action is simply too high for the guitar to be comfortable to play. I am going to remove the neck, alter the neck geometry, and set it back in place. Guild guitars have taken on legendary reputation for being difficult to disassemble. Let's see if this one lives up to its name. This article is dedicated to the countless Guild acoustic guitar owners whose guitars have desperately needed a neck reset.

We assume that every guitar ever made had its neck set properly prior to being offered for sale. While we can certainly hope for that to always be the case, it is, unfortunately, a false assumption. The numbers are relatively small, thankfully, but many brand new guitars have needed a neck reset right off of the showroom floor to be optimized for performance. In such cases, a neck reset is necessary to correct a mistake, one made during initial construction. In most cases, a neck reset is needed to correct for glue failure and/or structural failure that has occurred later on in the guitar's life.

To better understand why I would ever need to deal with glue failure and/or structural failure in my acoustic guitar, let alone be faced with having to the remove the neck, adjust its geometry, and re-attach it, it really helps to learn more about how my guitar is constructed, the forces that are working on and against it, and the various factors that constitute a proper "setup."

Woods from various sources, dried and having varying degrees of moisture content, assembled using a variety of adhesives, patterned after a variety of designs, and touched by an untold number of workers, man and machine included, become what we will affectionately refer to as "our (current) favorite guitar."

There are dozens of steps that must be taken to produce an acoustic guitar (roughly 30 to 80), depending on what you define as a step. The end result can be measured qualitatively as the sum total of the steps. Design considerations aside (actually thinking that a given design is already perfect and cannot be improved upon), believing that each of those steps is performed with accuracy, precision, love and care on each and every instrument ever made is more than a bit naïve. My point? Things can and do go wrong. Often.

When tightened to pitch, guitar strings exert anywhere from 150+ lbs to 250+ lbs of pull between one end of the guitar and the other, seemingly seeking to fold the guitar in half. Considering the reality that most guitars are subjected to all kinds of temperature and humidity shifts, and depending on who built what, when and how, it is not unreasonable to expect something to change in may guitar over time. In fact, it is unreasonable not to. When such change is sufficient, a neck reset is required to re-establish correct geometry.

If each and every component of a wooden acoustic guitar simply stayed put, precisely where it was placed when the guitar passed its initial Quality Control inspection, no guitar would ever require a neck reset. And there would be no need for truss rods. And saddles would never need to be lowered. But things don't always stay in place. Over time, and subjected to various environmental changes, things move away from their original locations.

So what?, you may ask. So, what if everything isn't perfect, and things have moved a bit? What determines whether I need a neck reset, or not?

In a word, playability.

Playability is a highly subjective term, inspiring debates over such incendiary, highly subjective topics as:

Left in a hot car, glues soften and guitars come apart. But you already know that. Beyond the obvious issue of heat damage, there are parallels that can be drawn between guitar and automobile ownership, and this may be helpful in gaining a different perspective regarding neck resets on acoustic guitars.

People ride in or drive automobiles that they rent, lease, or own for all sorts of reasons. For most of us a car (or truck or van) is a necessity. For some, it is just a tool. For others, it is a status symbol or even a toy. Still others see it as a commodity to be bought and sold for profit. And there are those who would prefer to accumulate as many vehicles as possible, and perhaps one day charge admission to view them. And there are many other reasons.

Regardless of the reasons for driving or owning a car, these vehicles are going to require servicing at some point. Some service items are relatively minor, while others are not. Keep a car long enough, or inherit it from someone else who kept it long enough, and certain things will have to be addressed. Consider the following (suggested) parallels:

| Automotive | Guitar |

|---|---|

| Washing | Cleaning |

| Waxing | Polishing |

| Garaging | Casing |

| Tune-ups | Setups |

| Tires | Frets and fretboard |

| Collision repair | Brace re-glues and split cleating |

| Reupholstery | Refinish |

| Transmission or Engine overhaul | Guitar neck reset |

You are welcome to map your own parallels. My hope is that you see the relevance of comparison and realize that whether you view the inevitability of maintenance and repair to be a life-altering, traumatic encounter of ultimate devastation, and something to be avoided at any and all cost, or just another thing you need to take care of, is entirely your choice.

A neck reset is one of those things that is going to be required at some point.

To determine whether my guitar requires a neck reset right now, or not, I need to focus on an aspect of playability known as "action," the height of the strings off of the fretboard. Action is an informative indicator regarding what is going on with my guitar.

Action - String Height Above Fretboard

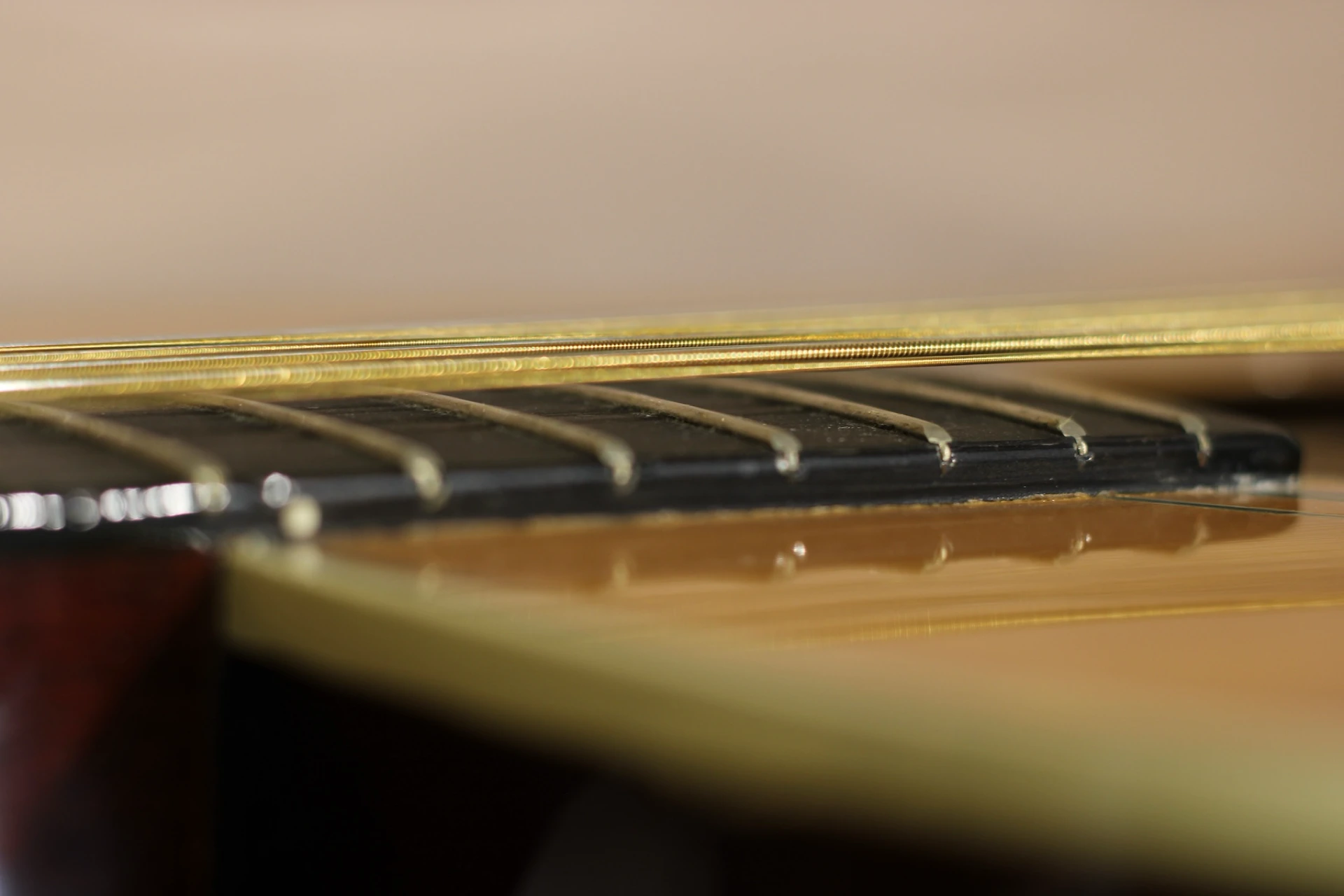

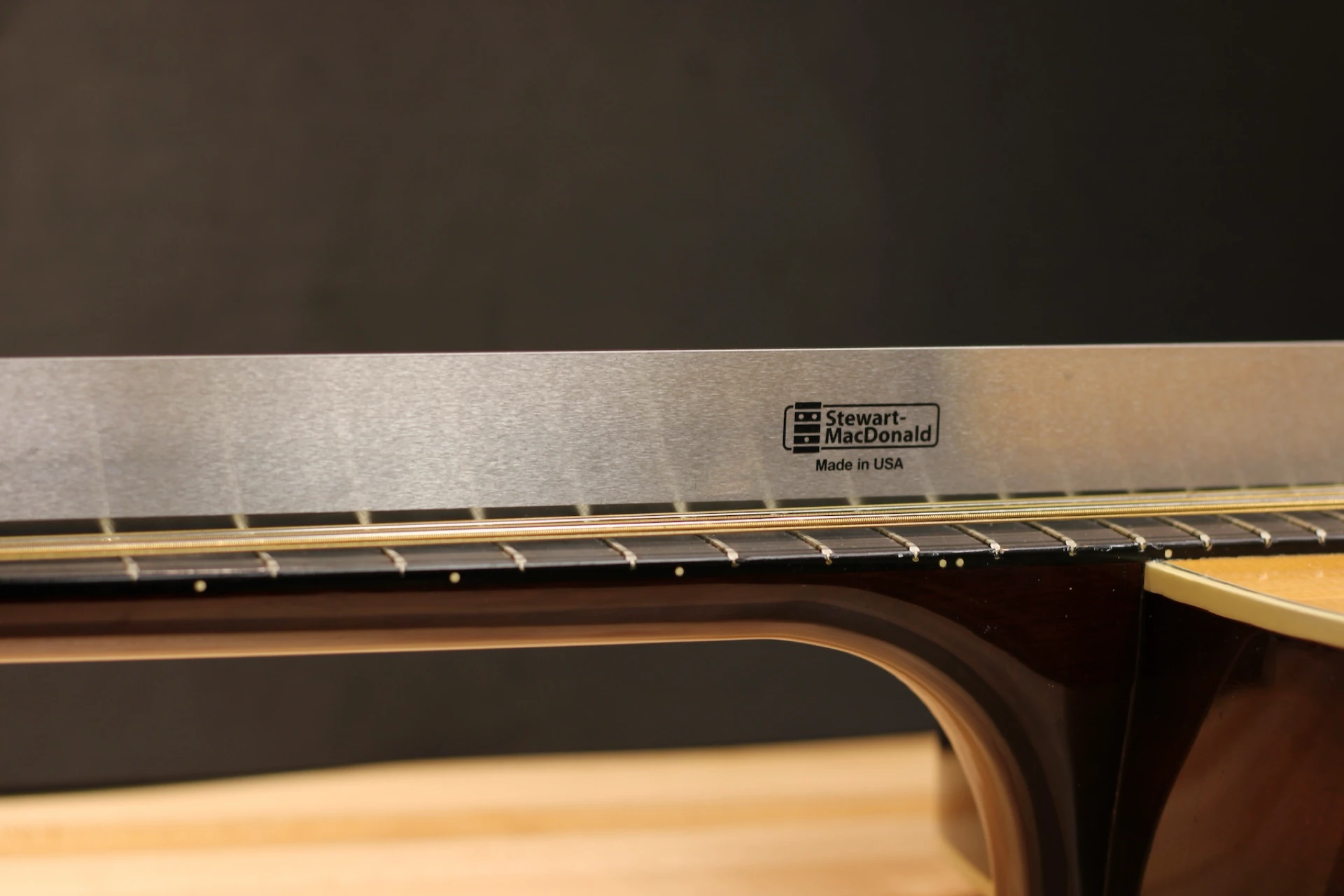

Before attempting to address action and conduct a corresponding setup (which includes fret height, nut slot height, and saddle height), let alone prior to beginning any dramatic neck alterations, it is necessary to have a reference against which changes can be measured. That reference is a perfectly flat (aka "dead-flat") fretboard (fingerboard). I need to get the fingerboard into a flat plane, first. I say fingerboard, not neck, as the surface of the board is my reference.

There is a popular assumption that the surface of the fingerboard is (or can be made to be) a perfectly flat plane, and the frets installed on that flat plane are all of perfectly consistent height. This assumption has resulted in extreme frustration being experienced by many a luthier and/or guitar technician. While that *may* be the case, and we hope it is the case, it is unwise to proceed under the assumption it is without verifying.

Fingerboards may vary in thickness and/or flatness, which may be accidental or deliberate. I have performed many a fret job simply because it was easier for me to pull the frets and address the surface of the board directly. Naturally, frets have to be put back and, since I have gone this far, why not replace the old frets with new metal?

Assuming I know what I'm doing, if my attempts to complete a proper setup on my guitar result in the strings either laying on the fretboard buzzing, or being so far away from the fretboard that they cannot be fretted (depressed to make contact with the metal frets) without significant effort and corresponding discomfort/pain, it is highly probable that my guitar requires a neck reset.

One benefit of a proper setup can be viewed as a remediation of the string height issue to improve playability. It involves steps such as correcting neck bow and/or twist, flattening (planing) the fretboard and re-fretting with taller or shorter frets, dialing in the correct nut slot depth, raising or lowering the saddle height, correcting bellying, correcting bracing failure or collapse, installing the greatest strings in the world, etc. If all these steps fail to make the guitar playable again, it may be time for a neck reset.

A wooden guitar neck is essentially a straight plane. I say essentially, as a given guitar neck may have just the slightest amount of forward bow in it, depending upon a player's preference for relief. Relief refers to a deliberate introduction or allowance of concavity along the surface of the fingerboard/fret plane in an attempt to mitigate string buzz, the result of the strings contacting the metal frets as they oscillate. Additionally, the fretboard extension, that part of the fretboard that extends beyond the point where the neck joins the body, may include fall-away. This is a slight, but deliberate sloping of the fretboard away from the path of the oscillating strings.

On a guitar having a perfectly flat neck, depending on the overall stiffness of the neck and the gauge of the strings, some forward bow will likely occur due to the pull of the strings. If additional bow is desired, more relief can be introduced by planing, carving or sanding material away from the fretboard, or by bending the entire neck forward using an internal mechanical device: the truss rod. When plucking or strumming the strings, a very light string attack requires little or no relief, whereas very aggressive string attack may require greater relief.

Check for Neck Bow

Many guitars, upon inspection, have necks that appear to suffer from excessive bow, often forward but sometimes backward. Excessive back (convex) bow will cause the strings to lay on the fretboard against the frets, making the guitar unplayable. On guitars whose necks have a single action truss or compression rod, it may be possible to simply loosen the tension on the rod and allow the strings to pull the neck forward enough to counteract the back bow. If the neck is equipped with a dual-action truss rod, it is usually possible to deliberately bow the neck forward. If the neck continues to curl backward, the condition of the neck will need to be addressed, first.

Excessive forward (concave) bow, a visible curling forward of the neck, will raise the action to a point where the guitar quickly becomes unplayable. Most modern guitar necks are equipped with a means of countering the pull of the strings on the neck, and an excessive forward bow may be able to be corrected by tightening the truss rod in the neck. If such corrections fail to make the guitar playable, a neck reset is probably in order.

Occasionally a neck will twist enough that one side or the other is raising the strings much higher than it should. Looking down the fretboard from one end of the guitar or the other and comparing the plane of the headstock/nut against the plane of the bridge/soundboard should help to confirm or alleviate any suspicion of twist. In some cases, the bridge has been planed or sanded into a wedge shape, either originally by design or during some re-design, intervention, repair, etc. If so, it is the plane of the soundboard alone, not the top of the bridge, that I must compare with the plane of the nut in order to determine if I am dealing with neck twist, or not.

Neck Twist Check - Nut

Neck Twist Check - Saddle

Severe twist may or may not be correctable. In lieu of straightening or replacing a twisted neck, sometimes cleverly messing with the geometry of the neck, body, bridge, and saddle is sufficient to keep a guitar playable without killing the sound. Sometimes.

Some necks are simply not straight to begin with; as in, they cannot even be forced into a flat condition. Such necks need to be addressed, separately, as a neck reset is not the proper solution. Before giving up on a troublesome neck, it is worth investigating whether it is the neck or the fretboard that is causing the problem. Sometimes a fretboard can be replaced more readily than an entire neck.

Removing the frets and flattening the fretboard lets me literally start from a level playing field (pun intended). This is the right time to address the condition of the overall fretboard, adjust the radius, increase or reduce fall-away, and determine the optimal fret height and fret material for the replacement frets.

If my action is really high, and I lower the height of my frets, the result is an even higher action. Sometimes, by installing taller frets and thereby reducing the distance between the tops of the frets and the bottoms of the strings, I can put off resetting the neck just a bit longer.

Once I know my neck/fretboard is straight, my next step in setting up proper action is to address the nut slots. This step pertains to fretboards whose nut acts as fret zero. The difference between a guitar that feels like a wire cheese slicer on my fingertips and a fretboard that "plays like butter" starts at the nut slots, specifically, in the distance between the top of the first fret and the bottom of the string as it rests in its respective slot in the nut. There should only be enough distance (the slots should only be close enough to the fretboard) to prevent the strings from resting on the first fret. A common test that can be conducted without using measuring tools (such as a dial indicator or feeler gauges) is to depress each string against the 3rd fret and "tap" each fretted string against the 1st fret. I am hoping to see only the slightest gap between the fretted string and the top of the 1st fret. Anything more than that is an opportunity to lower the nut slot.

Saddle height is not arbitrary, at least not if I am wanting my guitar to be all it can be. Reaching for the sandpaper to shorten the height of the saddle, in an effort to lower the action to make my guitar easier to play, may not be the best solution if I am expecting maximum volume and optimum tone from my guitar. Assuming my neck/fretboard is flat, and assuming the strings are properly seated in nut slots that have been filed to the proper height (as low as they can go without buzzing), and assuming the saddle slot in the bridge is both cut to proper depth for that bridge and is perfectly flat across the bottom, the amount of saddle that extends above and beyond the top of the bridge should be determined by the necessary height of the strings off of the soundboard, not the fretboard.

To produce both maximum volume and optimum tone, it is necessary to achieve maximum and optimum height of the strings off of the soundboard in front of the bridge. Establishing the string height for player comfort is the primary role of the neck geometry, not the saddle.

To that end, you may see the benefits of having an easily adjustable neck, such as a bolt-on neck, where the neck joint can quickly be altered and shimmed. Action can be adjusted at the neck joint, leaving the saddle and bridge to perform at their respective peaks.

The bridge of my guitar is external brace, adding stiffness to the soundboard. The bridge of my guitar is fixture, providing me with a means of attaching the strings, as well as holding the saddle in place. The bridge of my guitar is an acoustic coupler, transmitting the kinetic energy of the plucked and oscillating strings across the soundboard. The bridge of my guitar is part 1 of a 2-part unit, the bridgeplate being part 2. This unit sandwiches the soundboard and works together to add stiffness, hold the strings, and transmit string energy.

As with the saddle, bridge size (height, width, weight, and mass) is not arbitrary. The bridge must be sized correctly to perform its tasks well. Too large or too small of a bridge will make for poor sound output. The mass of the bridge is relative to the responsiveness of the internal bracing and soundboard. Making changes to the height of an existing bridge via planing or shaving it down in order to preserve saddle exposure may not be the optimal solution for my particular guitar.

Break angle is a term that refers to the angle at which the string, emerging from the bridge (or tailpiece), "breaks" across the saddle as it continues its path to the nut. There is an additional break angle that can be identified as the string leaves the back of the nut in a trajectory to the post of the machine head (tuner), but that is a separate topic. Having sufficient break angle as the string leaves the back of the saddle is essential, but probably not for the reason you are accustomed to hearing about.

In order to experience maximum sonic output from a given acoustic guitar, the measured angle of the string breaking over the saddle is of much less importance than is the overall height of the string off of the soundboard. The torque applied from sufficient string height will actually "rock" the bridge forward and back in response to the force applied (energy transmitted) as the string oscillates. Break angle serves to "lock" the string down over the crest of the saddle, such that any shifting and rolling from side to side on the part of the string(s) is eliminated or minimized. Rather than being wasted, maximum energy can then be transmitted down into the bridge.

On a guitar whose saddle has been lowered to the point where it is essentially buried in the saddle slot, the player may experience a terrifically weak output, where both volume and tone suffer markedly. A taller saddle may be a remedy, but for the fact that action height will then become untenable. If this is the case, a neck reset is probably in order. This is rather easy to prove: if you have a guitar with a nearly non-existent saddle, install a taller saddle, one that is standing at least 1/8 inch above the bridge. String up the guitar and, realizing that the action is obviously now painfully high, have a listen. I believe you will hear something that is much closer to what your guitar should be sounding like.

Bridge Lift

Bridge lift describes a visible gap between the soundboard and the back of the bridge. Such a gap may or may not require attention. Most guitar bodies have a finish applied prior to attaching the bridge. For a proper bond, the bridge needs to be glued to the raw wood surface of the soundboard, not the surface of the finish. To that end, the finish is either carefully removed or prevented from ever being applied in the area where the bridge will lay. It is quite common to leave a small border of finish around the periphery of the bridge, just enough for the bridge to rest on and provide for a clean visual intersection, as opposed to removing finish to the outside edge of the bridge, which would reveal an unsightly trace line all around the bridge. If (or as) the bridge rocks or tilts slightly forward, and depending on several other factors, including how wide that border of finish under the backside of the bridge is, a gap may or may not appear along the back edge, and that gap may or may not be stable for the life of the instrument.

Allow me to make what should not be a controversial statement: Bridges should not require re-gluing; unlike fret wear, for example, this is not a common maintenance item.

A significant gap behind the bridge is an indication that something has gone wrong, either as a result of a slow process of failure due to poor materials or construction in the very beginning, or perhaps more sudden damage (like leaving a guitar in the hot car). The strings will likely be raised much higher off the fretboard than they should be. In the simplest of cases, where glue failure is due to insufficient glue and/or loose bracing, glue and clamping may be all that is needed to restore a guitar to playability. In some cases, such as an oily bridge that glue is refusing to bond well with, or too large of a finish border beneath the bridge, it may be better to completely remove the bridge in order to first address those issues. The above are best case scenarios. It may be that the soundboard is too thin or is in process of shearing due to severe grain run-out, or the bracing is simply insufficient to prevent the buckling that is contributing to the bridge lift. More dramatic steps may be necessary to mitigate a catastrophe.

It bears repeating that the thickness of an acoustic guitar bridge, also referred to as its height, is not (rather, should not be) an arbitrary measurement! Employing a production-minded technique certainly not unique to Guild, many guitar makers of yesteryear assembled their instruments by first attaching the necks to the body, and then selecting/making/modifying a bridge to fill the space between the soundboard and the plane of the fretboard (already established by the attached neck). With bridge height being the only criteria, it is easy to understand (years later) why the same model instrument could have such significantly audible distinctions from siblings produced on the same assembly line.

The bridge of an acoustic guitar is a multi-functional component. The bridge is (typically) responsible for pinning the strings in place. The bridge supports the saddle. The bridge, the only exterior brace on the soundboard, in conjunction with the bridgeplate, forms a unit that is responsible for transmitting kinetic energy generated by the plucked string(s) onto and across the soundboard, which is sandwiched between the two. It is crucial for the mass of a given bridge (taking into account the mass of the bridgeplate beneath it) to be sufficient to drive the top, to set the soundboard in motion. It is quite easy to rob the sonic life out of a guitar by adding or modifying a bridge that is improperly sized. Too small or too light a bridge will produce a very weak output. Likewise, too large/too heavy of a bridge can either act to dampen transmitted energy or completely overdrive the top.

Assuming the goal is to achieve the maximum sonic potential of a given soundboard, a crucial factor in determining the optimum size/mass of its bridge/bridgeplate is the overall stiffness of that soundboard after bracing. Overall soundboard stiffness will be determined by the material(s) used in the construction of the soundboard, as well as by the pattern, dimensions, and stiffness of the bracing.

The bridge must first be matched to the soundboard on which it will reside, and then the neck geometry can be determined. Not vice-versa.

If, in order to stave off the apparently inevitable neck reset and to keep the instrument playable, overall string height has been lowered by reducing the bridge’s height (by planing or "shaving"), it is quite possible that the bridge is now undersized. This typically translates into a quieter, lackluster sounding guitar. Efforts to improve the tone and/or volume, such as increasing the string gauge (moving from lights to mediums, or from mediums to heavy gauge), replacing plastic bridge pins with bone, or replacing bone bridge pins with brass or titanium, will be short-lived solutions. The fix is in - to restore such a guitar it will now be necessary to remove both the neck and the bridge, pair a new bridge (and possibly bridgeplate) with the soundboard, and reset the neck.

Bellying describes a condition where the lower bout section of the soundboard, the part directly behind the bridge, is pulled markedly upward by the tension of the strings. This is typically the result of the bridge rocking slightly forward, and can be due to several factors:

Bridge lift may accompany bellying, though not always. Is bellying ever acceptable? More than one luthier thinks so, with the maxim, "No belly, no tone" being echoed by both pros and novices, alike. If so, how much bellying is “too much?” Slight to modest bellying is simply the result of the pull of the strings on the bridge and the related structural integrity of a given guitar that resists the tendency of that string pull to fold the instrument in half. So long as everything stays in place, all is well and may remain so for the life of the instrument.

However, if the belly increases, it is quite possible that something is (or several "somethings" are) wrong. The string action will have been raised, as either the bridge is now tilting forward like a surfer catching a wave, or the entire soundboard is lifting. Resetting a neck on such an instrument may be a short-lived solution, as that belly may not be done lifting. Prior to assuming a neck reset is immediately necessary, it may be prudent to first address the belly bulge. Where bellying is the result of components having shifted away from their original positions, it is possible to "flatten" that belly using heat with a series of cauls. Sometimes bracing can be (or should be) re-glued and this is sufficient to deflate a bulging belly. Where bellying is the result of insufficient bracing and/or a soundboard does not have sufficient stiffness to stay flat, more drastic measures may be called for. Only after addressing bellying should you proceed with a neck reset.

In my experience, the primary culprit behind the need for Guild neck resets is the shifting of the neck block, the worst case scenario resulting in the shearing of the soundboard along the fingerboard extension on one or both sides. The soundboard does NOT have to split along the fingerboard extension for the neck block to have shifted, though it is probably only a matter of time...

I have written extensively about this topic, and rather than repeat it again here, you can read all about this in my article titled,Neck Block Shift and Soundboard Shear.

Thankfully, there is no evidence of splitting in this particular soundboard, yet, nor has the neck block provided me with any indication of failure.

Guild Dovetail Joint

Guild acoustic guitars, particularly older models, are somewhat legendary among repair shops, the consensus being that neck resets are more difficult to perform on a Guild than on other guitars. The Guild brand is among those who did not switch to bolt-on mortise and tenon necks, choosing to retain the more traditional glued-on compound dovetail joint. To reset a neck, it is first necessary to remove it. Guild necks were first attached to the body, and then the finish was applied. This complicates the removal process and adds the need for touch-up efforts once the neck is re-applied.

I stumbled across a great quote from Ireland's Gerry Hayes of Haze Guitars (https://hazeguitars.com), that perfectly expresses the common sentiment regarding the topic of Guild neck resets:

"Neck resets, therefore, range from relatively-easy (Taylor NT necks), to a-bit-more-hassle (bolt-on necked guitars) to break-out-the-steamer-and-the-tea (Martins), to break-out-the-steamer-and-the-whiskey (Gibsons), to oh-god-not-a-bloody-Guild (Guilds)."

The Finish - To remove the neck, the lacquer “seal” must first be broken. After the neck is reset, that lacquer must then be touched up. This can be complicated by a tinted finish, though it isn't a particular nightmare in and of itself. If, by extreme contrast, you have ever reset a Taylor neck (bolt-on, no lacquer touch-up necessary), you would understand the extra work involved on a Guild neck, along with the additional equipment and skills requirement.

The Glue - If you have reset enough Martin necks you may have run across that occasional instrument where it seems as though you could simply pull the neck off after exhaling a warm sigh across the heel. If you were to then encounter any one of the several Guild necks where any and all open space in the neck joint has been thoroughly flooded with glue, you would likely conclude that Guild neck resets can be more difficult to remove.

Some Guild necks are more difficult to remove than others, although few, if any of the ones I have encountered from the 1970s and up through 2010 have ever been as easy to remove as the bulk of Martin necks I have removed from the same period. Unfortunately, I cannot provide anyone with an authoritative list of which Guild guitars are more difficult than others, as it remains a mystery even to me until after I have started on a removal.

At issue is the amount of glue applied in the neck joint, and the surfaces to which the glue has been applied. All that should be required of a properly fitted compound dovetail joint is a brush (or fingertip) stroke of glue along the two sides of the tail. The purpose of the adhesive is merely to prevent the tenon from sliding upward in the mortise, the reverse direction from which it was “set.” The one and only possible reason I can think of for applying copious amounts of glue to a dovetail joint, other than ignorance (not knowing any better), is to compensate for a sloppy fit. So, rather than take the time necessary to correct the actual problem, the loose fit, someone just adds more glue to hold the neck in place.

You may have heard someone speaking about neck angle and/or neck geometry and wondered what they were referring to. In addition to the shape, width, thickness, and overall weight of a given acoustic guitar neck, the angle of incidence at which that neck joins the guitar body is a critical factor in both realizing the sonic potential of the guitar and determining its playability.

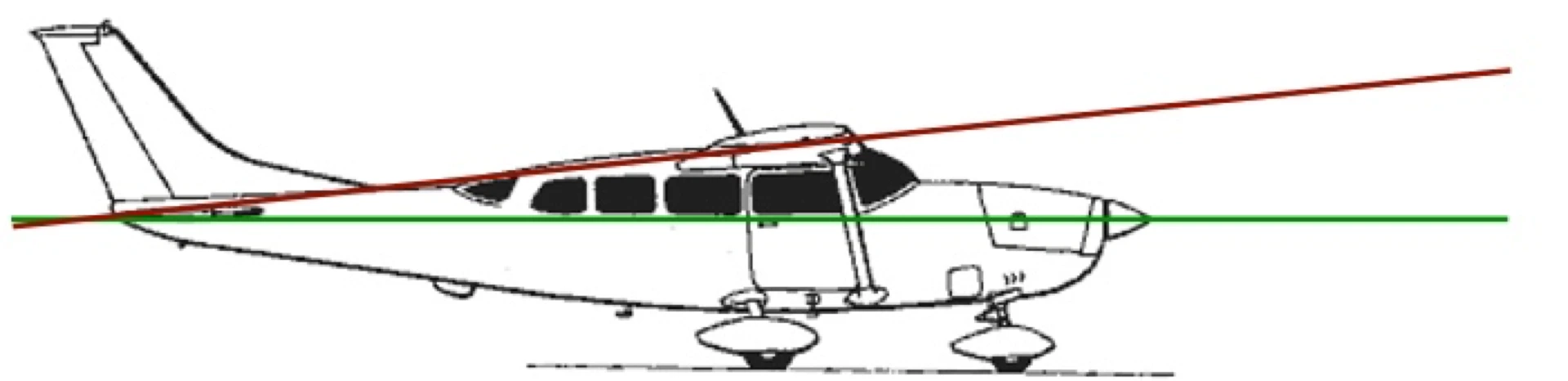

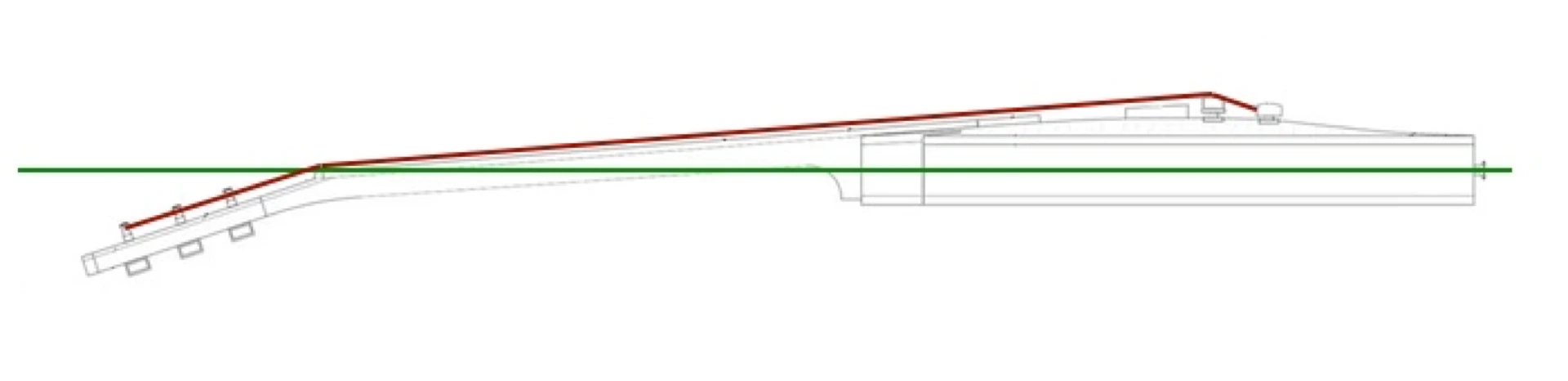

On an aircraft, such as the high-wing Cessna in the drawing below, the Angle of Incidence between the chord of the wing (imagine a straight line drawn through the center of the leading and trailing edges, shown by the red line) and the longitudinal axis of the body (shown by the green line) can be clearly seen.

Cessna wing Angle of Incidence

When applied to the guitar, there are two angles of incidence that can be considered. The first is the plane (as in planar, not aircraft) of the neck and/or neck/headstock in relation to the plane of the body. The second is the string path in relation to the body and neck.

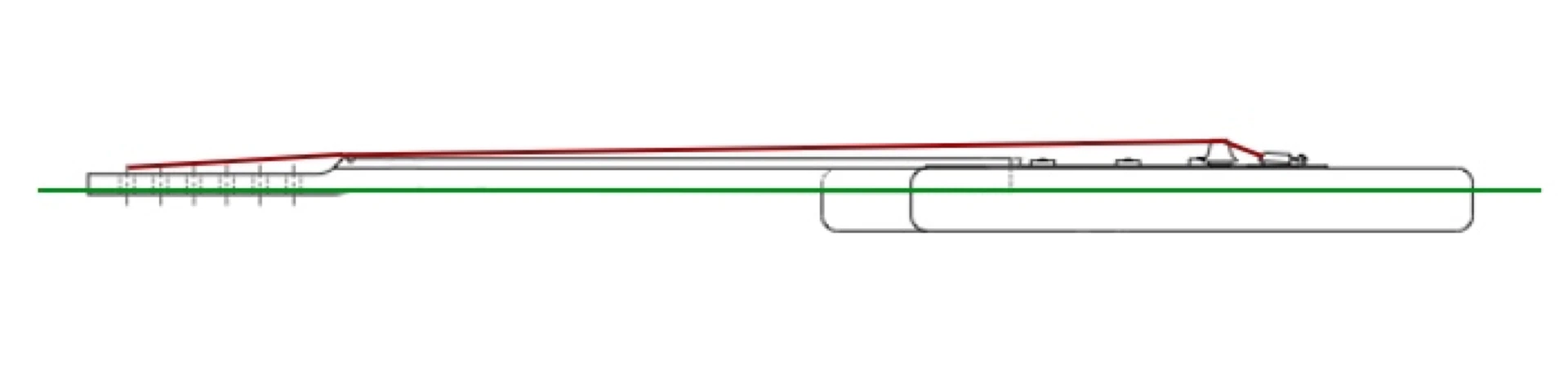

Consider the side profile of a Fender Stratocaster. The longitudinal axis of the body is shown by the green line. The red line shows the string path. Notice how the neck, body, and headstock are all in parallel with the longitudinal axis of the body. The "chord" formed by the string path in relation to the longitudinal axis of the neck/body unit demonstrates a very shallow angle of incidence.

Fender Stratocaster

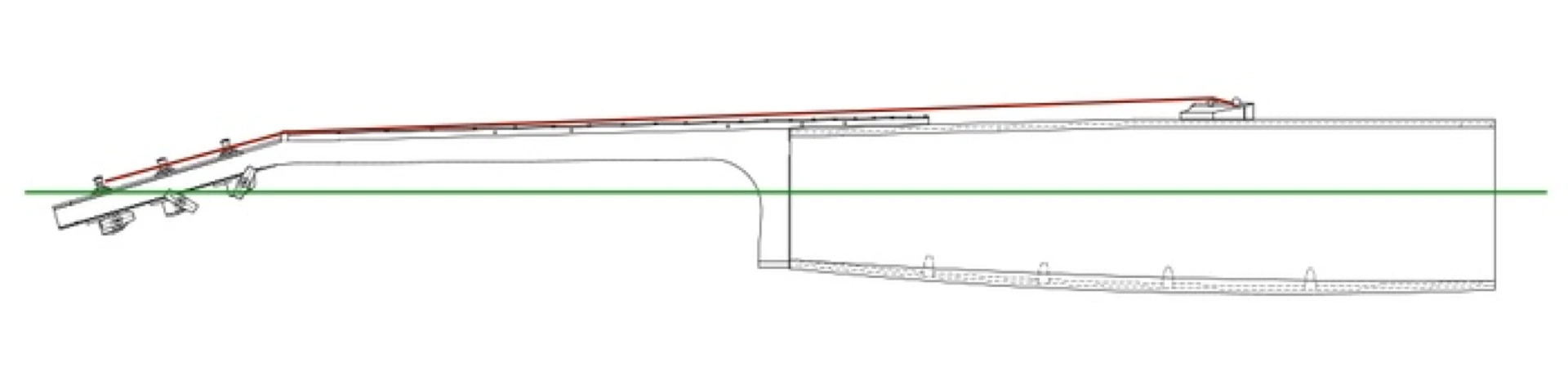

Contrast the Fender Stratocaster with the Gibson Les Paul. Again, the longitudinal axis of the body is shown in by the green line, and the red line follows the string path. Note how the neck deviates from the longitudinal axis of the body, and the headstock deviates from the longitudinal axis of the neck. Compared with the Strat, the "chord" formed by the string path in relation to the longitudinal axis of the neck/body unit demonstrates a sharper angle of incidence.

Gibson Les Paul

As you can see, the angle of incidence of the typical acoustic guitar neck, as well as the angle of incidence of the typical acoustic guitar string path sits comfortably in between the Les Paul and the Strat. The angle of incidence of both the neck and the string path of an acoustic favors that of the Strat, where the angle of incidence of the headstock of an acoustic is more akin to that of the Les Paul.

Acoustic Guitar

The angle at which the neck joins the body is not arbitrary; it is intrinsic to the design of that guitar. Failing to target the optimal neck angle, an under-set or over-set neck will negatively affect playability, at the very least, and actually affect the overall tonal quality of the instrument.

What, exactly needs to be corrected in order to improve playability?

Bolt-on or glue-on? How to apply heat.

Break the seal. Bolt-on or glue-on? Steam? Heat Stick?

Mortise and Tenon, Dovetails and compound angles

Materials, Optimal size

Proper fitting, glue choices

Proper fitting, glue choices