By the winter of 2014, my 1980 Guild F-412 12 string was in need of a neck reset. A straightedge, when placed on the fretboard, plowed down toward the top of the guitar contacting the bridge well below its top surface. Over the years the saddle had been lowered repeatedly and the bridge had been shaved (planed, to allow more saddle to be exposed) as the top had bellied and the neck had pulled forward. A JLD Bridge System had been applied internally and was marginally successful in adding a few more years of playability. The string height above the fretboard had grown too tall for my taste, and no more adjustments could be made to compensate for the problem. The time had come to put things right.

I removed the Bridge Doctor, fearing the worst. With the strings back on, I measured the top deflection at a point just behind the bridge to contrast with the measurement taken after the strings were removed, and found the differences to be surprisingly nominal, at approximately 0.030″. To accomplish this, I use a bar fixed with a dial indicator and two legs. The legs rest on opposite rims of the lower bout, hold the bar parallel with the plane of the soundboard.

Though slightly bellied, the top was remarkably stable, likely due to the presence of Guild's three monster tone bars (braces butted against the X brace and tapering out toward the tail of the guitar, stopping just short of the rim) glued to the underside of the top, behind the bridge. Deflection measurement (if there is any) is taken into consideration when determining how much material to remove from the neck heel to correct the neck angle.

NOTE: It is possible to take measurements from an unstrung guitar, reset a neck, re-string the guitar and, as the strings pull the top up, discover the new neck angle is insufficient. That is a mistake that usually only happens once.

In order to begin to correct the string height issue, it would be necessary to slightly increase the angle of the neck back away from the top of the guitar. This adjustment also (ever-so-slightly) alters the distance from the nut to the saddle, also known as the scale length. Under optimal circumstances a new saddle might be shaped to compensate for the scale length variance. Equally often though, a new saddle slot needs to be routed at a new, precise location, requiring the existing slot to first be filled in. In my case, however, with both the scale length changing and the fact that the bridge is much thinner than desired due to shaving, the bridge needs to be replaced.

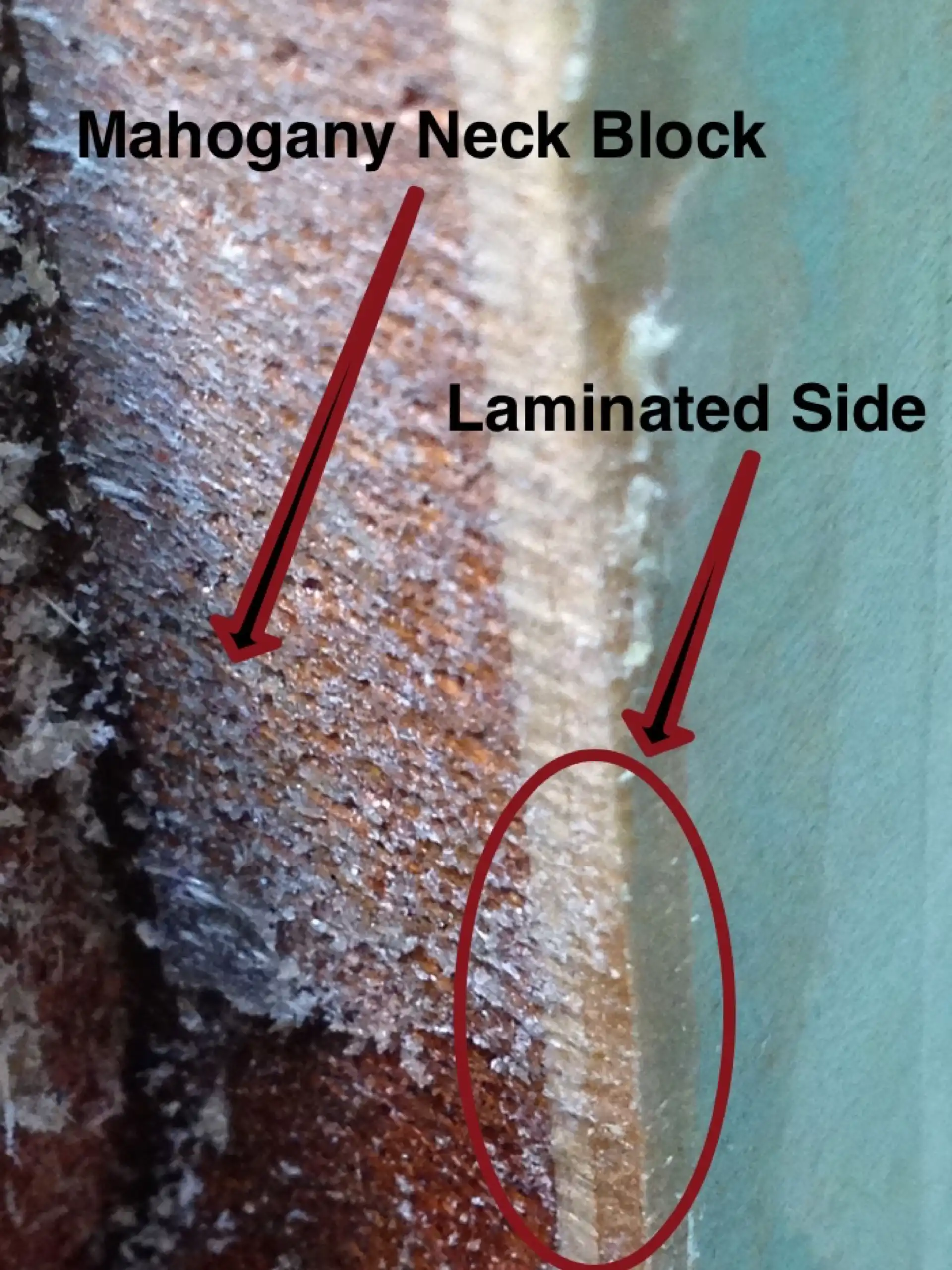

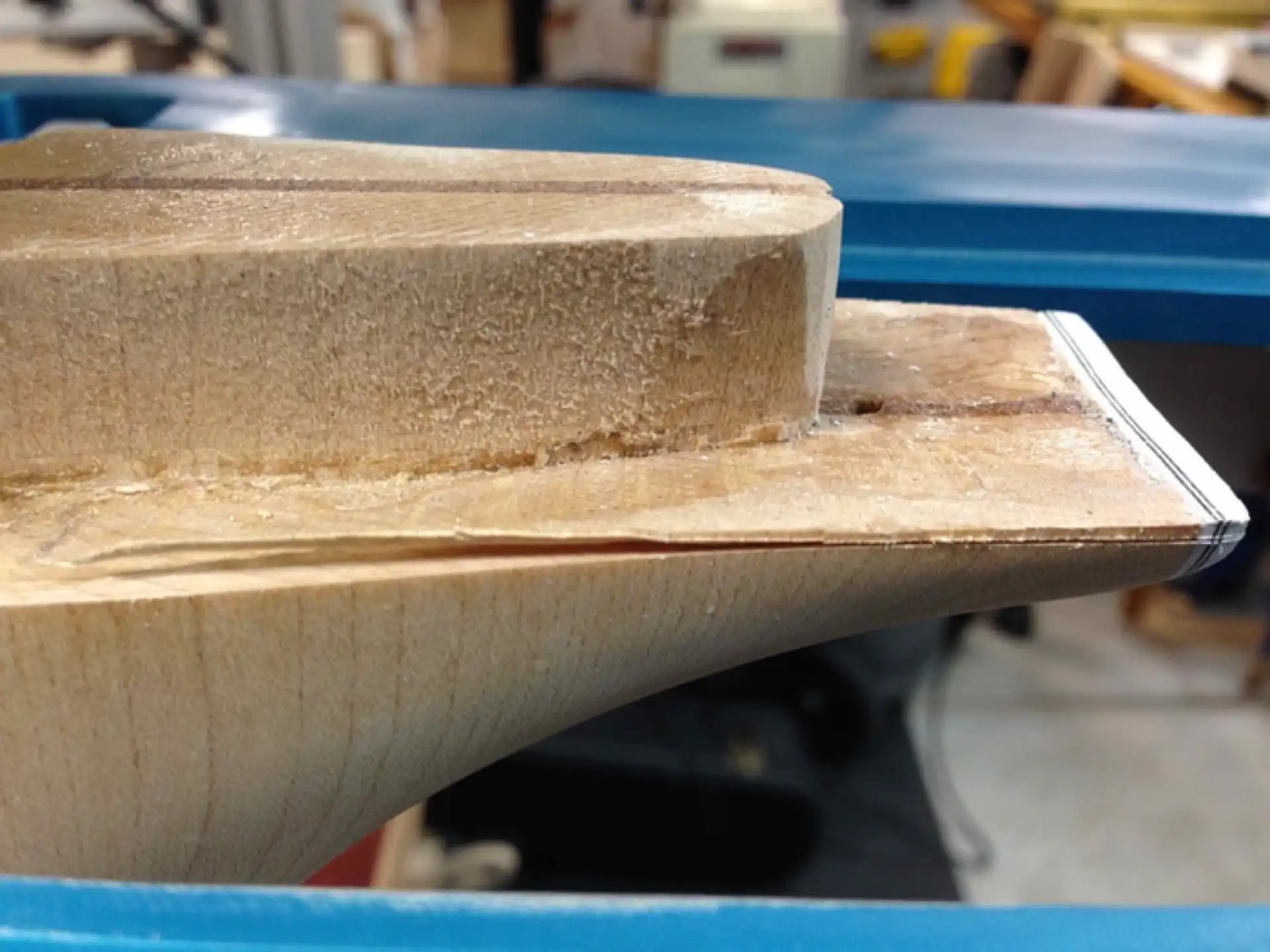

This particular Guild F-412 was constructed with laminated Maple sides, a laminated Maple arched back and a three-piece Maple-Walnut-Maple neck. This cross-section view of the side (seen from the neck block dovetail mortise) reveals the two-ply lamination that makes up the sides.

Laminated Maple Sides

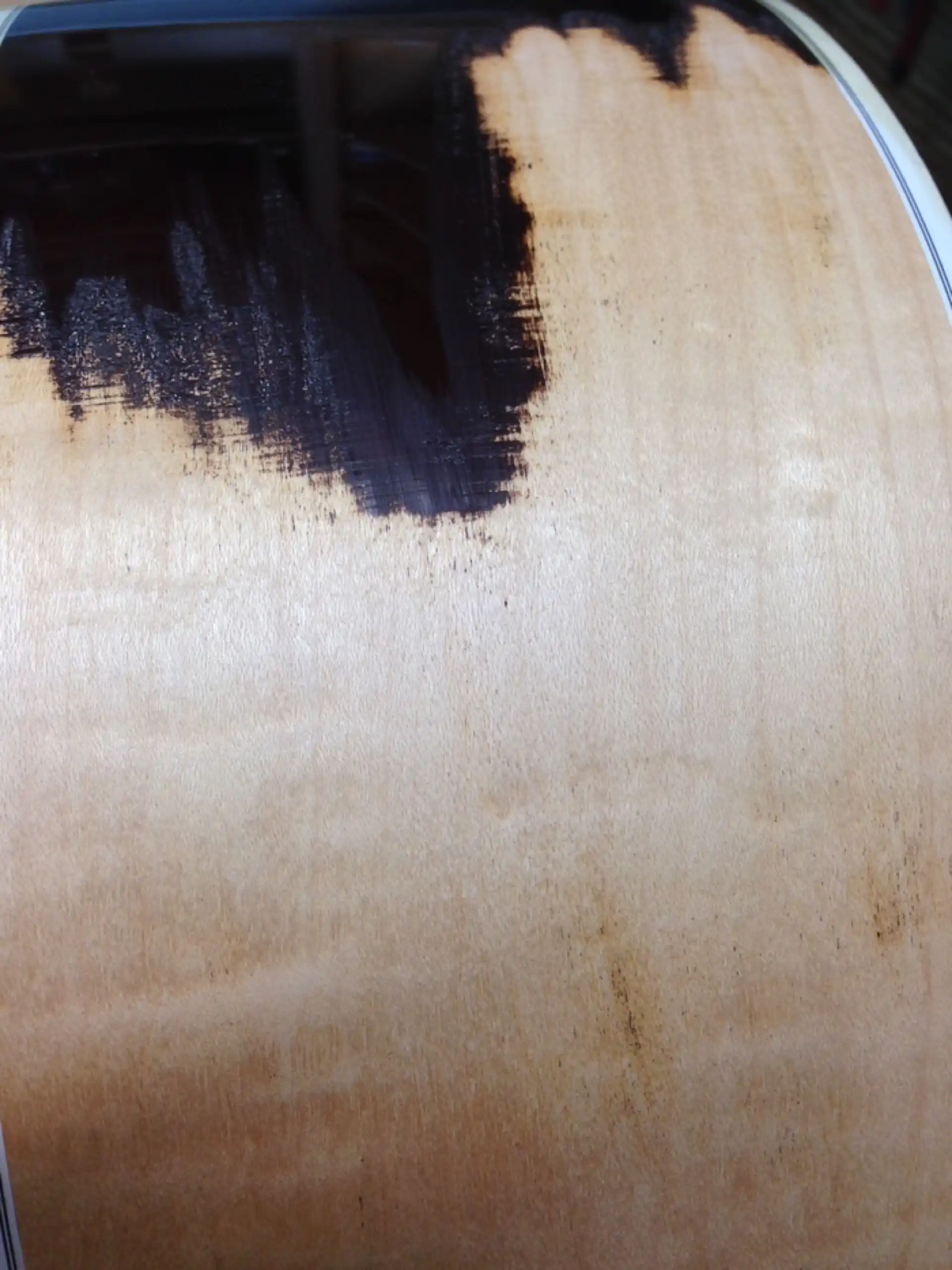

The guitar had been finished with a tinted nitrocellulose lacquer (NCL), the color being referred to as Cabernet at the time, and top-coated with a clear lacquer. In 35 years, the clear finish had yellowed significantly (in my case as a result of plenty of exposure to sunlight). Cabernet plus yellow = brown. Not all that pretty. I had always wondered just what the tinted finish was hiding and I determined that one day I would find out.

F-412 Back

Unlike the finish on my 1976 Guild F-50R which looked like a shattered windshield (thanks to my flights back and forth to Alaska), this 1980 F-412 had suffered no finish checking, though it showed wear and tear, having a handful of nicks, dings and scratches. Was the finish hiding one or more flaws (as was often the case with these instruments)? I really wanted to see the original wood grain. Since I would be removing the neck in order to alter the neck angle, I decided that now was as good a time as any to tackle a re-finish.

I would be using a sharpened scraper for removal of the nitrocellulose lacquer finish.

A scraper provides me very tactile feedback of my progress. Granted, it takes some elbow grease, but the results are consistently pleasing and achieved with minimal disturbance of the underlying wood.

I laid the guitar face down on my bench, donned a mask, broke out my scraper, held my breath (figuratively speaking) and scraped up my first ultra-thin ribbons of lacquer. The top coat, as expected, was clear (albeit yellowed) lacquer.

F-412 Clear Lacquer

Subsequent scrapings revealed the darker, tinted lacquer that made up the initial darker coat(s).

F-412 Tinted Lacquer

And then I hit pay dirt! The golden curly Maple that was barely visible beneath the finish and hadn’t breathed oxygen for three and a half decades suddenly leapt into view.

F-412 Maple

A view of the back of the headstock provides a hint at just how much scraping is necessary to peel away the finish.

F-412 Back of the headstock

2 hours later (and some serious neck, shoulder, arm, hand and finger work that left me begging for a massage) and I was left wondering why this Maple had been covered in the first place. While certainly not breathtaking, it looked just fine (Methinks our standards have been lowered over the years). I was relieved to not find any real flaws in the Maple on the body and delighted at the prospect of seeing a clear finish go back on this guitar.

F-412 Maple Back

F-412 Maple Back Closeup

The thin finish of the neck scraped off readily, and revealed the only notable aesthetic “flaw” on the entire guitar, a 2″ streak of discolored wood on the backside of the neck, near the headstock. This flaw is not a surface stain and the (already completed) dimensions of the neck will not be disturbed so it will remain “as is” with no attempt made to hide it.

I would venture to guess that, in a production setting, this flaw alone may have contributed (if not driven) the decision to add this guitar to the list of guitars to be tinted, contrasted with the majority of instruments that would be clear-coated.

F-412 Maple Neck Flaw

The ebony-colored fiberboard head plate with mother-of-pearl inlay scraped down perfectly smooth. It will look great, once re-finished. I removed and re-glued the binding around the headstock, something I had wanted to do for a long time.

Satisfied with the results thus far, I set out to remove the neck. Using my high-tech fret removal tool (a soldering iron) I heated the 15th fret (one fret wire closer to the soundhole than the point where the neck joins the body) and carefully removed it with nippers. Heating the fret helps to minimize chip out of the brittle ebony, as the barbed fret tang is forced up and out. Those barbs aren't designed for fret removal, so they do tend to grab, tear, fracture and chip the wood on their way up and out.

F-412 Steam Holes

Here is view of the access holes that get drilled to introduce steam (or dry heat). You are looking at the underside of the fretboard extension *after* the neck has been removed:

F-412 Steam Holes Underside

Something of an urban legend has developed over the decades regarding a notion that Guild dovetailed guitar necks are somehow generally more difficult to remove than other manufacturer’s dovetailed necks. Is there any truth to this claim? Yes and no. If a luthier has restricted to application of glue to a small smear on either side of dovetail, then the experience of removing the neck is pleasant, regardless of brand.

Here is where things get interesting. Guild neck heels, by design, are wider than Martin neck heels where they meet the body. That should not translate to anything significant *unless* that heel is also be glued to the sides of the body. Having a wider dovetail would likewise not translate to anything of significance *unless* one is unnecessarily adding glue into the dovetail cavity (the space between the end of the tail and the wall of the neck block). With some instruments, glue was applied so liberally that it filled that small space in the mortise, entombing the dovetail in glue. A neck assembled this way would result in much greater effort being needed to remove it. Happily, such was not the case with this particular Guild.

I attached a neck removal jig to the body. Its purpose is to apply pressure to the heel of the neck at the end cap, to un-wedge the compound angle of the triangular tenon from its corresponding mortise. Depending on the guitar, it can be prudent to remove the end cap from the heel or leave it in place. I opted for the latter (and was glad I did once I saw how the neck had been prepared for its initial glue-up). Steam is introduced into the glue joint via a hollow metal tube attached to a hose which, in turn, is attached to a high-quality European steam source (a cappuccino machine - ha-ha), through the two holes drilled in the fret slot. I propped up the guitar to allow any water (cooled, condensed steam) to drain down and away from the body of the instrument, as opposed to letting it run onto (or worse, into) the body.

F-412 Steam

NOTE: A telltale sign of a neck reset, especially one where more hot water than steam has been used, is the presence of dried white powdery rivulets of watery glue residue inside the body of a guitar. I will not be introducing any.

Alternating the steam between holes while gently increasing pressure against the end cap was sufficient to break the neck loose. Time elapsed: Less than 5 minutes total with approximately 2 teaspoons of water on the bench.

F-412 Steam

I towel dried all the parts and inspected the joint. Everything looked good. This was a clean neck removal.

I spent another hour carefully scraping and sanding to remove any remnants of lacquer from the neck and body, and then moved on to the soundboard. I had left the finish in place during the application of steam, as it would offer a degree of protection should any water hit the top.

I heated the ebony bridge (a heat gun, heat lamp, hot iron or even a hair dryer will work) to soften the glue. Care must be taken to not overheat the surrounding areas, as other glue joints (bridgeplate, braces, top to sides, binding, etc.) need to stay intact. Some very thin tools (palette knives) were used to release the bridge from the underlying Spruce. Hardwood bridges are glued directly to unfinished, softwood tops (at least, they *should* be). When removing a bridge it is important to work slowly and deliberately to minimize any tear out of the soundboard.

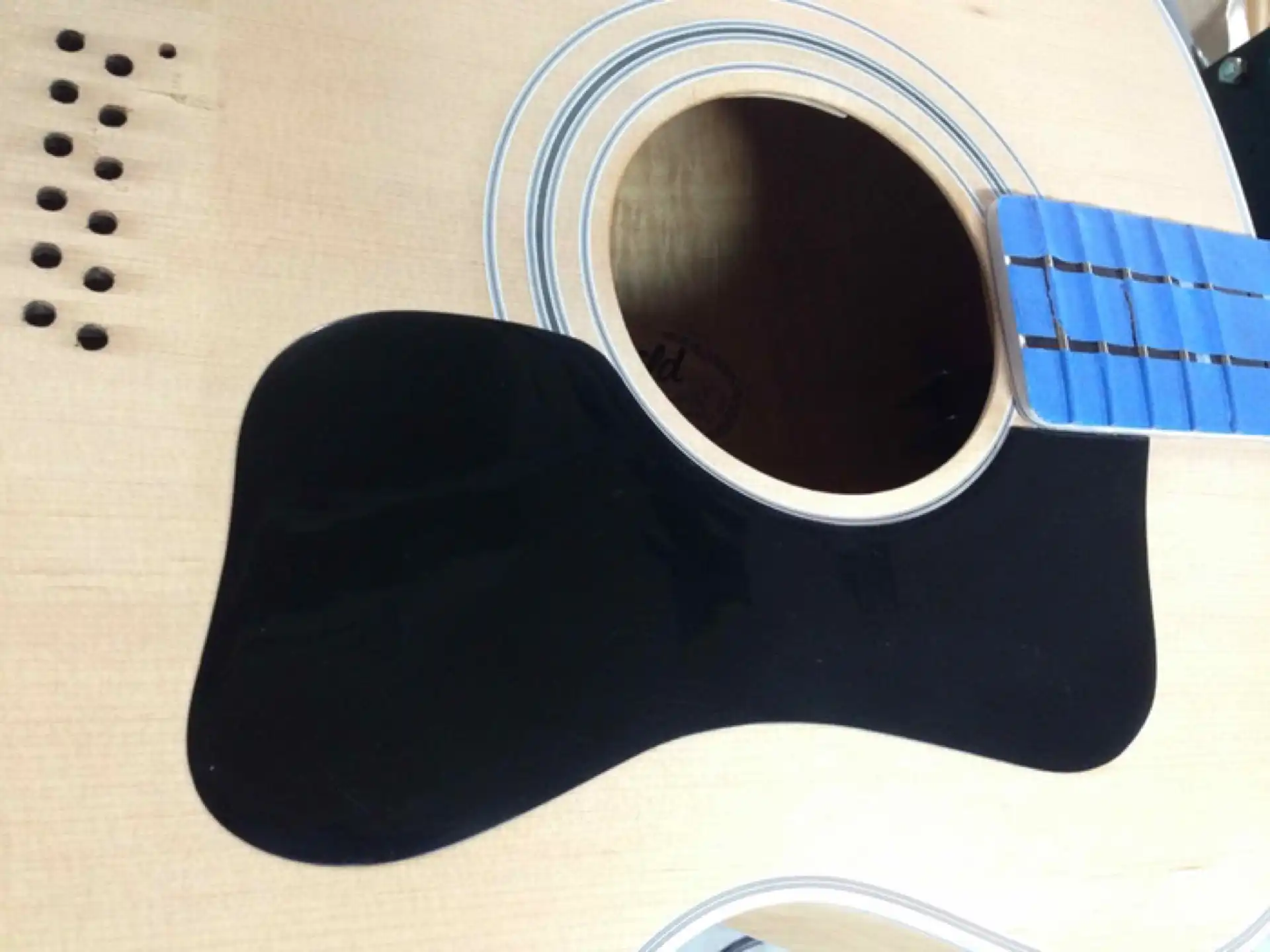

The same process removed the pickguard, which did result in some tear out. Unlike the bridge, which must be glued to the raw wood surface of the soundboard for longevity, a pickguard *should* be attached to the surface of the finish, not the surface of the raw, unfinished wood. With adhesives not being as advanced back in the era of the construction of these guitars, pickguards were fused directly onto the soundboards, and are extremely difficult to remove. In my case, lifting the pickguard away from the top also revealed some serious grain runout in the Spruce. I will be replacing the pickguard, which will cover any blemishes.

I spent a bit more time improving the condition of the white plastic binding which was (evidently) a bit irregular to begin with. There were a couple of cracks in the binding around the fingerboard but, as they were stable, I chose to leave them alone. Solvent-based plastics will shrink over time and, when they do, they can leave some nasty scars.

With the fingerboard, bridge and pickguard removed from the body it was a simple task to carefully remove the finish from the Spruce top. It was important to just take off the finish, not the underlying wood, since a top’s thickness plays a major role in determining its stiffness and, subsequently, both its sound and its strength. With that task accomplished, I wiped a coat of Shellac over the top to offer some protection as I continued to work with the guitar.

The old pickguard was in bad shape, so I took the time to sand out the flaws and polish it to a mirror shine. This is what it would look like if I chose to reuse it (a classic Guild appearance):

F-412 New Pickguard

Traditionally, these incredibly tough celluloid pickguards were fused into the underlying wood by using either lacquer thinner or a solvent-based adhesive (since they are made of a solvent-based plastic), then a lacquer finish was sprayed over the top. Celluloid will shrink (breaking down over time), and if you saw how well glued/fused to the Spruce this type of pickguard can be, it would be easy to understand why so many vintage soundboards have cracks or splits below the pickguard. The pickguard shrinks as the solvents flash off over the years, ripping and tearing the wood it is directly fused with away from the adjoining wood. Thankfully, that had not occurred to this 12 string. Traditionally, to re-affix the celluloid pickguard I would need to apply a solvent-based adhesive and fuse the pickguard back into the wood. But I have options: I can affix the old pickguard over the finish, but I can also simply make a new black pickguard from a non-shrinking material. It can be black or even a faux tortoise-shell look (see photo, below).

My 12 string originally came with an ebony bridge, where some F-412’s of that time shipped with rosewood bridges. I decided to stay with the original look, with the headplate, fingerboard and bridge all being of the same wood, so I hand-planed a piece of ebony square, thickness sanded it, traced the old bridge, cut it on the bandsaw, sanded to the traced lines and shaped the wings. I will wait to produce the saddle slot until after the new bridge is glued in place, as I wish to alter the compensation that had been established for the guitar, originally.

F-412 New Bridge and Pickguard

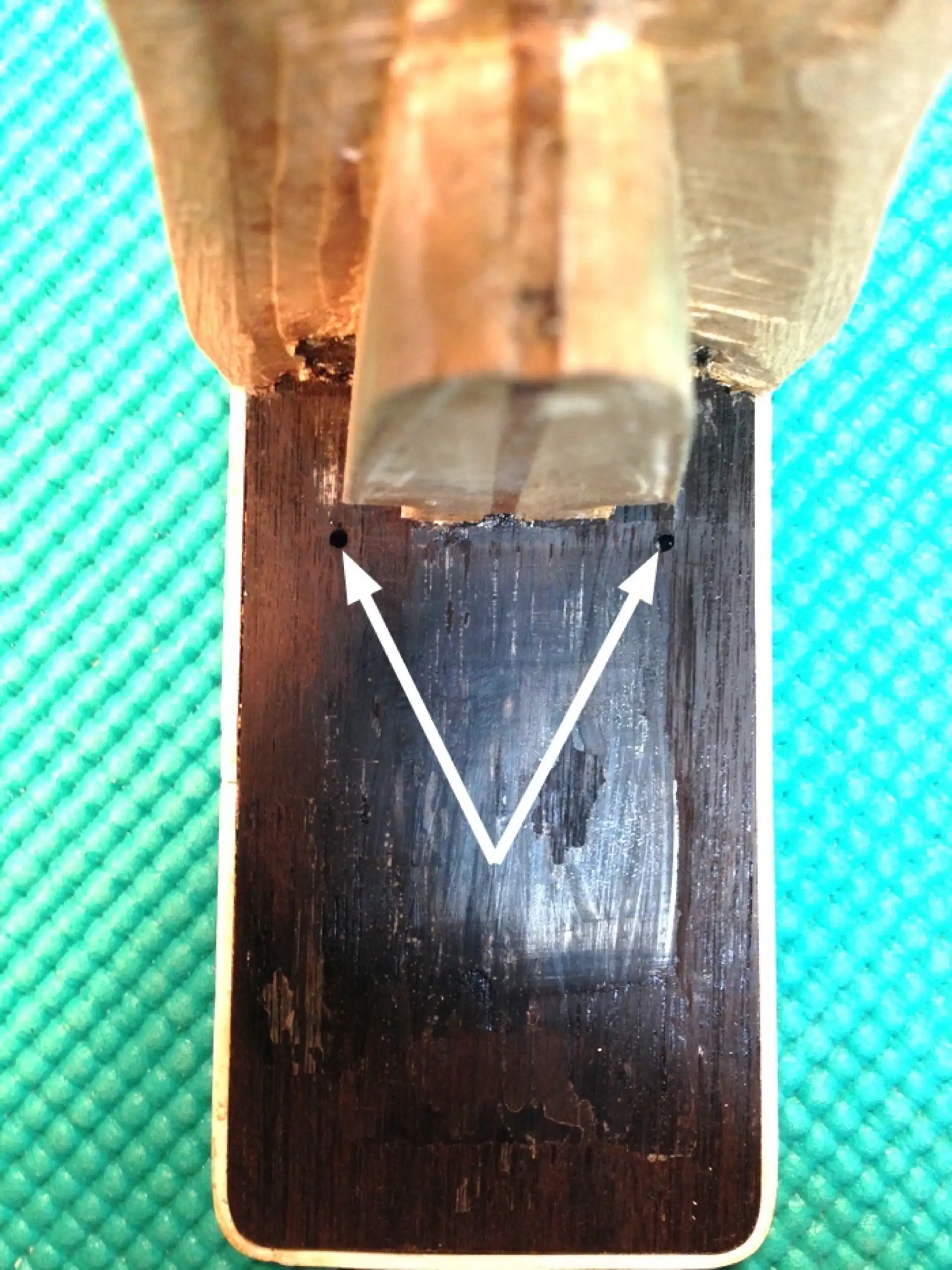

Using the top deflection measurement I took prior to removing the neck, along with the length of the neck heel and the distance from the nut to the center of the 14th fret, it was possible to calculate the amount of material I needed to remove from the base of the heel to angle the neck correctly. This Guild neck heel was thin to begin with, so great care had to be taken when removing even more material. The neck is hard Maple, so my marking and cutting tools have to be razor sharp! The photo, below, clearly shows how more material is removed from the base of the heel, and no material is removed from the intersection of the top of the heel and the surface of the neck. This taper tilts the neck, dropping the headstock, and angling the flat plane of the fingerboard upward over the surface of the soundboard.

F-412 Remove Material

The heel rests against the sides of the body. There should be no gap(s) between the two components. Under near perfect conditions, the surface of the body and the surface of the heel are planar, and the two mate together seamlessly. In the real world, there are variations in those surfaces that result in unsightly gaps. How do I overcome the variations? Sandpaper.

As I am going to be removing very small amounts of material from the neck heel, there is no need for me to have to sand the entire surface of the heel. I will remove material using a chisel, leaving a small ledge around the perimeter of the heel. This will be what I sand.

F-412 Material Removed

With the guitar body held firmly in place, I set the tenon of the neck into the mortise of the neck block, and deliberately pinch a piece of sandpaper between them, sand side up. Using an iterative process, beginning with the sandpaper on one side of the dovetail, holding the neck firmly against the body, I draw the sandpaper out from beneath the heel. I repeat the process, placing the sandpaper on the opposite side of the dovetail. I then test fit the neck without any sandpaper.

I will lather, rinse, and repeat until any and all gaps are resolved. I am careful to A.) not alter the neck geometry I have just cut into the heel, and B.) remove material form both sides of the neck evenly, checking to ensure the string path stays centered on the bridge.

F-412 Fitting the Neck

The bridgeplate was in remarkably good condition (I can make a fairly decent argument for being careful with string changes), and all bracing remained intact so no internal repairs were necessary. I taped off the location of the bridge in order to have bare wood to re-attach the new bridge to, and then it was time to get started on the finish prep.

The neck and body were sanded to 320 grit for a perfectly smooth, scratch-free surface. It is important to not "scrub" the wood (especially a softwood top such as Spruce or Cedar), generating heat as though burnishing, as that seems to merely pack the dust into the surface and alters the look of the wood. For a glossy finish on furniture that can be advantageous. For a musical instrument it can be detrimental. Wiping with naphtha is helpful to reveal any flaws, as well as to remove residual dust.

The back, sides and neck of this 12 string are Maple, making pore filling unnecessary. I had considered experimenting with the finish, using a special Shellac on this 12 string, a formulation that adds cross-linking hardeners and a plasticizer, but there are many other options including more durable waterborne Urethanes, various oil-based finishes, a CyanoAcrylate finish, and good ol’ NitroCellulose Lacquer.

The new bridge was glued on using non-creeping hide glue, whose working time is measured in seconds rather than minutes. With that kind of time constraint it is imperative to have a dress rehearsal or practice run prior to applying any glue. The bridge is clamped in place, any squeeze out is wiped up immediately, and the bridge is left to dry.

New pickguards typically come with an adhesive backing and are applied over the top of the finish.

A new nut is fashioned for the headstock end of the fretboard.

Using a fixture, the precise compensated position of each string is transferred onto the bridge. This allows for precise positioning of the routed saddle slot.

A new saddle is fashioned for the bridge, the machine heads are re-attached to the headstock, the guitar is strung and tuned to pitch, and the overhaul of this 1980 Guild F-412 is complete!